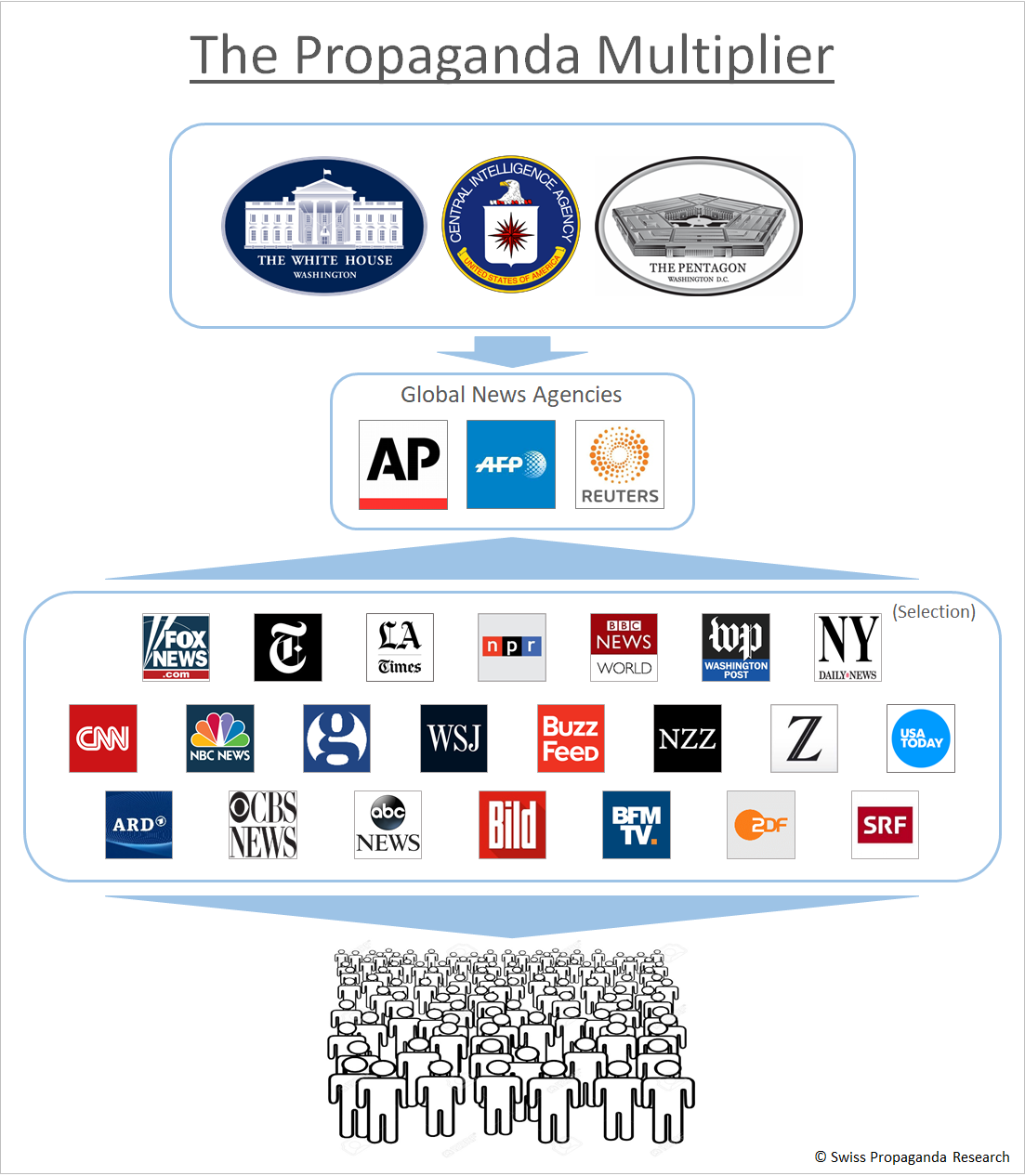

The Propaganda Multiplier

Most news coverage is provided by three global news agencies. AP, AFP and Reuters.

Ask yourself: Why do I get this specific information, in this specific form, at this specific moment? Ultimately, these are always questions about power.

Dr Konrad Hummler, Swiss Banking & Media Executive

A study by Swiss Policy Research found most international news coverage is provided by 3 global news agencies based in New York, London and Paris.

Their role played by these agencies means Western media often report on the same topics, even using the same wording. Governments, military and intelligence services use these global news agencies as multipliers to spread their messages.

How Global News Agencies & Western Media Report Geopolitics

How does a newspaper know what it knows? The answer is likely to surprise some readers:

“The main source of information is stories from news agencies. The almost anonymously operating news agencies are in a way the key to world events. So what are the names of these agencies, how do they work and who finances them? To judge how well one is informed about events in East and West, one should know the answers to these questions.”

Höhne 1977

“News agencies are the most important suppliers of material to mass media. No daily media outlet can manage without them. So the news agencies influence our image of the world; above all, we get to know what they have selected.”

Roger Blum 1995

In view of their importance, it is astonishing that these agencies are hardly known to the public: “A large part of society is unaware that news agencies exist at all … In fact, they play an enormously important role in the media market. But despite this great importance, little attention has been paid to them in the past.”

Schulten-Jaspers 2013

They are little known to the public. Unlike a newspaper, their activity is not so much in the spotlight, yet they can always be found at the source of the story.

The Invisible Nerve Centre of the Media System

So what are the names of these agencies at the source of the story? There are now only 3 global news agencies left:

Associated Press (AP) has over 4,000 employees worldwide. The AP belongs to US media companies and has its main editorial office in New York. AP news is used by around 12,000 international media outlets, reaching more than half of the world’s population every day.

The quasi-governmental French Agence France-Presse (AFP) based in Paris with around 4,000 employees. The AFP sends over 3,000 stories and photos every day to media all over the world.

British agency Reuters in London, is privately owned and employs over 3,000 people. Reuters was acquired in 2008 by Canadian media entrepreneur Thomson – one of the 25 richest people in the world. It merged into Thomson Reuters, headquartered in New York.

In addition, many countries run their own news agencies. These include, the German DPA, the Austrian APA, and the Swiss SDA. When it comes to international news, national agencies usually rely on the three global agencies and simply copy and translate their reports.

Small Abbreviation - Great Effect

However, there is a simple reason why the global agencies are virtually unknown to the general public. To quote a Swiss Media Professor: “Radio and television usually do not name their sources, and only specialists can decipher references in magazines.” (Blum 1995, P. 9)

News outlets are not particularly keen to let readers know that they haven’t researched most of their contributions themselves.

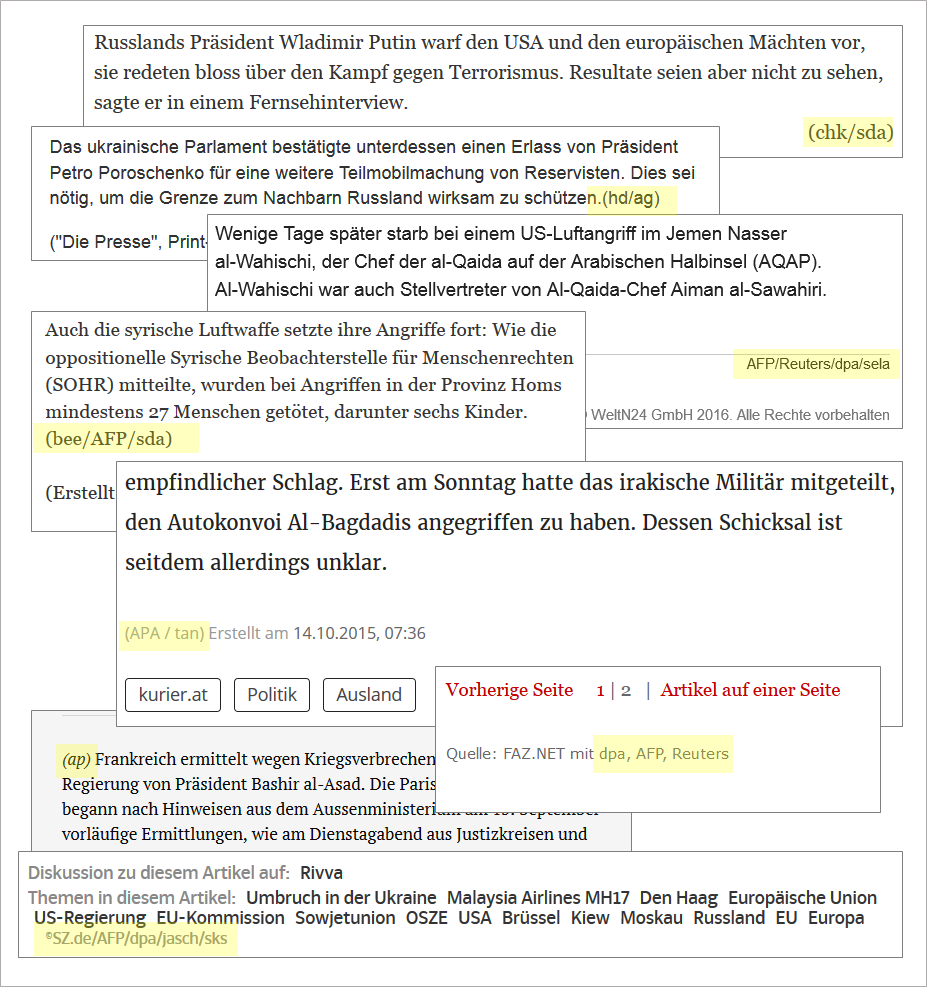

The following figure shows some examples of source tagging in popular European newspapers. Next to the agency abbreviations we find the initials of editors who have edited the respective agency report.

Occasionally, newspapers use agency material but do not label it at all. A study in 2011 from the Swiss Research Institute for the Public Sphere and Society at the University of Zurich came to the following conclusions (FOEG 2011):

“Agency contributions are exploited integrally without labelling them, or they are partially rewritten to make them appear as an editorial contribution. In addition, there is a practice of ‘spicing up’ agency reports with little effort: for example, unpublished agency reports are enriched with images and graphics and presented as comprehensive articles.”

The agencies play a prominent role not only in the press, but also in private and public broadcasting. Confirmed by Volker Braeutigamfn who worked for the German state broadcaster ARD for 10 years and views the dominance of these agencies critically:

“One fundamental problem is that the newsroom at ARD sources its information mainly from three sources: the news agencies DPA/AP, Reuters and AFP: one German/American, one British and one French. The Editor working on a news topic only needs to select a few text passages on the screen that he considers essential, rearrange them and glue them together with a few flourishes.”

Swiss Radio and Television too, largely bases itself on reports from these agencies. Asked by viewers why a peace march in Ukraine was not reported, the editors said: “To date, we have not received a single report of this march from the independent agencies Reuters, AP and AFP.”fn

Not only the text, but images, sound and video recordings that we encounter in our media every day are mostly from the very same agencies. What the uninitiated audience might think of as contributions from their local newspaper or TV station, are actually copied reports from New York, London and Paris.

Some media have even gone a step further and have, for lack of resources, outsourced their entire foreign editorial office to an agency. Many news portals on the internet publish agency reports: Paterson 2007fn Johnston 2011fn MacGregor 2013fn

In the end, this dependency on the global agencies creates a striking similarity in international reporting: from Vienna to Washington, our media often report the same topics, using many of the same phrases – a phenomenon that would otherwise rather be associated with »controlled media« in authoritarian states.

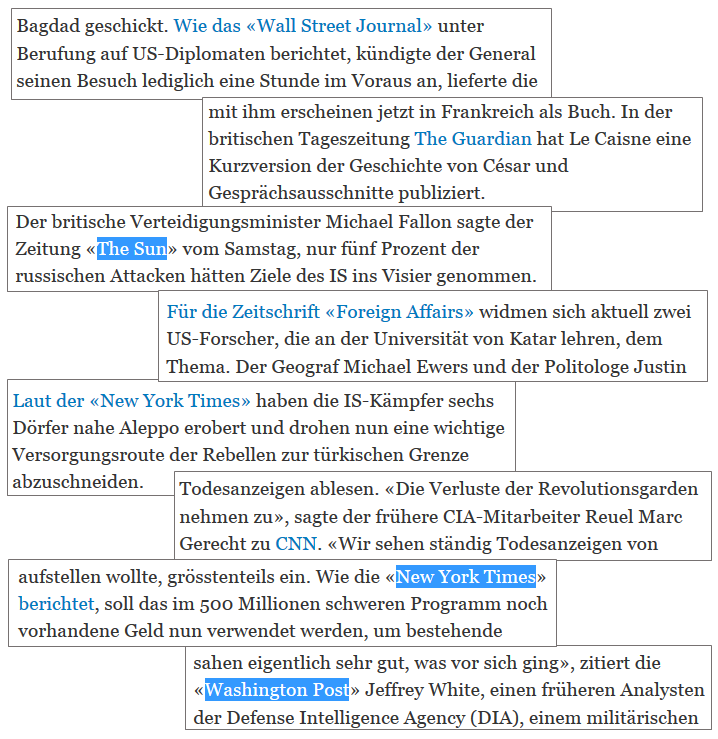

The following graphic shows some examples from German and international publications. Despite the claimed objectivity, a geopolitical bias sometimes creeps in.

The Role of Correspondents

Much of our media do not have their own foreign correspondents, so have no choice but to rely completely on global agencies for foreign news. But what about the big daily newspapers and TV stations that have their own international correspondents? In German speaking countries, these include newspapers such NZZ, FAZ, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, Welt, and public broadcasters.

In huge countries such as China or India, only one correspondent is stationed; all of South America is covered by only two journalists, while in even larger Africa no-one is on the ground permanently.

In war zones, correspondents rarely venture out. During the Syria war, many journalists “reported” from cities such as Istanbul, Beirut, Cairo or even from Cyprus. Many journalists lack the language skills to understand local people.

How do correspondents under such circumstances know what the “news” is in their region of the world? The main answer, once again: from global agencies. Dutch Middle East correspondent Joris Luyendijk described how correspondents work and how they depend on the world agencies in his book: People Like Us: Misrepresenting the Middle East:

“I had imagined correspondents to be historians-of-the-moment. When something important happened, they would go after it, find out what was going on, and report on it. But I didn’t go off to find out what was going on; that had been done long before. I went along to present an on-the-spot report.

The editors in the Netherlands called when something happened, they faxed or emailed the press releases, and I’d retell them in my own words on the radio, or rework them into an article for the newspaper. This was the reason my editors found it more important that I could be reached in the place itself than that I knew what was going on.

The news agencies provided enough information for you to be able to write or talk your way through any crisis or summit meeting. That’s why you often come across the same images and stories if you leaf through a few different newspapers or click the news channels.

Our men and women in London, Paris, Berlin and Washington bureaus – all thought that wrong topics were dominating the news and that we were following the standards of the news agencies too slavishly."

The common idea about correspondents is that they ‘have the story’, but the reality is that the news is from a conveyor belt. The correspondents stand at the end of the conveyor belt, pretending they've investigated themselves, while in fact all they’ve done is put it in its wrapping.

“Afterwards, a friend asked me how I’d managed to answer all the questions during those cross-talks, every hour and without hesitation. When I told him that, like on the TV-news, you knew all the questions in advance, his e-mailed response came packed with expletives. My friend had realised that, for decades, what he’d been watching and listening to on the news was pure theatre.”

Luyendjik 2009, p. 20-22, 76, 189

The typical correspondent is not able to do independent research, but rather deals with and reinforces topics already prescribed by news agencies – the notorious “mainstream effect”.

What the Agency does not report - does not take place

The central role of news agencies also explains why, in geopolitical conflicts, most media use the same original sources. In the Syrian war, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights – a dubious one-man organisation based in London – featured prominently. The media rarely inquired directly at this “Observatory”, as its operator was in fact difficult to reach, even for journalists.

Rather, the “Observatory” delivered its stories to global agencies, which then forwarded them to thousands of media outlets, which “informed” hundreds of millions of readers and viewers worldwide. The reason why the agencies, of all places, referred to this strange “Observatory” in their reporting – and who really financed it – is a question that was rarely asked.

The former Chief Editor of the German news agency DPA, Manfred Steffens, therefore states in his book The Business of News:

“A news story does not become more correct simply because one is able to provide a source for it. It is indeed rather questionable to trust a news story more just because a source is cited.

Behind the protective shield such a ‘source’ means for a story, some people are inclined to spread rather adventurous things, even if they themselves have legitimate doubts about their correctness; the responsibility, at least morally, can always be attributed to the cited source.”

Steffens 1969, p. 106

Dependence on global agencies is also a major reason why media coverage of geopolitical conflicts is often superficial and erratic, while historic relationships and background are fragmented or altogether absent. As put by Steffens:

“News agencies receive their impulses almost exclusively from current events and are therefore by their very nature ahistoric. They are reluctant to add any more context than is strictly required.”

Adding Questionable Stories

For deception manoeuvres, western militaries use the lack of transparency in media coverage. Picked up and distributed by newspapers and broadcasters, making it impossible for readers, listeners or viewers to trace the original source. Audiences fail to recognise the actual intention of the military.

In a report by British Channel 4, former CIA officials and a Reuters correspondent spoke candidly about the systematic dissemination of propaganda and misinformation in conflict reporting:

Former CIA officer and whistleblower John Stockwell said of his work in the Angolan War:

“The basic theme was to make it look like an [enemy] aggression. So any kind of story that you could write and get into the media anywhere in the world, that pushed that line, we did. One third of my staff in this task force were propagandists, whose professional career job was to make up stories and finding ways of getting them into the press.

The editors in most Western newspapers are not too skeptical of messages that conform to general views and prejudices. So we came up with another story, and it was kept going for weeks. But it was all fiction.”

Fred Bridgland looked back on his work as a war correspondent for the Reuters agency:

“We based our reports on official communications. It was not until years later that I learned that a little CIA disinformation expert had sat in the US embassy and had composed these communiqués that bore absolutely no relationship at all to truth. Basically, and to put it very crudely, you can publish any old crap and it will get into the newspaper.”

Former CIA analyst David MacMichael described his work in the Contra War in Nicaragua:

“They said our intelligence of Nicaragua was so good that we could even register when someone flushed a toilet. But I had the feeling that the stories we were giving to the press came straight out of the toilet.”

Of course, the intelligence services also have a large number of direct contactsfn in our media, which can be “leaked” information to if necessary. But without the central role of the global news agencies, the worldwide synchronisation of propaganda and disinformation would never be so efficient.

As the New York Times reported…

In addition to global news agencies, there is another source that is often used by media outlets around the world to report on geopolitical conflicts, namely the major publications in Great Britain and US.

News outlets like the New York Times or the BBC may have up to 100 foreign correspondents and additional external employees. However, as Middle East correspondent Luyendijk points out:

“Our news teams, me included, fed on the selection of news made by quality media like CNN, the BBC, and the New York Times. We did that on the assumption that their correspondents understood the Arab world and commanded a view of it – but many of them turned out not to speak Arabic, or at least not enough to be able to have a conversation in it or to follow the local media.

Many of the top dogs at CNN, the BBC, the Independent, the Guardian, the New Yorker, and the NYT were more often than not dependent on assistants and translators.”

In addition, the sources are often not easy to verify (“military circles”, “anonymous government officials”, “intelligence officials”) and can also be used for propaganda. The widespread orientation towards the major Anglo-Saxon publications leads to a further convergence in media.

The following figure shows some examples of such citation based on the Syria coverage of the largest daily newspaper in Switzerland, Tages-Anzeiger. The articles are all from the first days of October 2015, when Russia for the first time intervened directly in the Syrian war (US/UK sources are highlighted):

The Desired Narrative

But why do journalists in our media not try to research and report independently? Middle East correspondent Luyendijk describes his experiences:

“You might suggest that I should have looked for sources I could trust. I did try, but whenever I wanted to write a story without using news agencies, the main Anglo-Saxon media, or talking heads, it fell apart. Obviously I, as a correspondent, could tell very different stories about one and the same situation. But the media could only present one of them, and often enough, that was exactly the story that confirmed the prevailing image.”

Media researcher Noam Chomsky has described this effect in his essay “What makes the mainstream media mainstreamfn as follows:

“If you get off line, if you’re producing stories that the big press doesn’t like, you’ll hear about it pretty soon. So there are a lot of ways in which power plays can drive you right back into line if you move out. If you try to break the mould, you’re not going to last long.”

Some of the leading journalists continue to believe that nobody can tell them what to write. How does this add up? Chomsky clarifies:

“The point is that they wouldn’t be there unless they had already demonstrated that nobody has to tell them what to write because they are going say the right thing. If they had started off at the Metro desk... and had pursued the wrong kind of stories, they never would have made it to the positions where they can now say anything they like. The same is mostly true of university faculty in the more ideological disciplines. They have been through the socialisation system.”

Ultimately, this “socialisation system” leads to journalism that no longer independently researches and critically reports, but seeks to consolidate the desired narrative through appropriate editorials, commentary and interviews.

The First Law of Journalism

Former AP journalist Herbert Altschull called it the First Law of Journalism:

“In all press systems, the news media are instruments of those who exercise political and economic power. Newspapers, periodicals, radio and television stations do not act independently, although they have the possibility of independent exercise of power.”

In that sense, it is logical that our traditional media which are predominantly financed by advertising or the state – represent the political interests of the transatlantic alliance, given both the advertising corporations as well as the states are dependent on the transatlantic economic and security architecture.

In addition, key people leading media are often part of elite networks. Some of the most important institutions in this regard include the US Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), the Bilderberg Group, and the Trilateral Commission, all of which feature many prominent journalists.

Most well-known publications may be seen as a kind of “establishment media”. The freedom of the press is rather theoretical, given significant entry barriers such as broadcasting licenses, frequency slots, requirements for financing and technical infrastructure, limited sales channels, dependence on advertising and other restrictions.

It was only due to the Internet that Altschull’s First Law has been broken to some extent. In recent years a high-quality, reader-funded journalism has emerged, often outperforming traditional media in terms of critical reporting. Some of these “alternative” publications already reach a very large audience, showing that the “mass” does not have to be a problem for quality.

A good write up by Max Blumenthal on Reuters and BBC's Covert UK Program pushing a top level agenda worth reading here.