The Wall Street Bombing of 1920

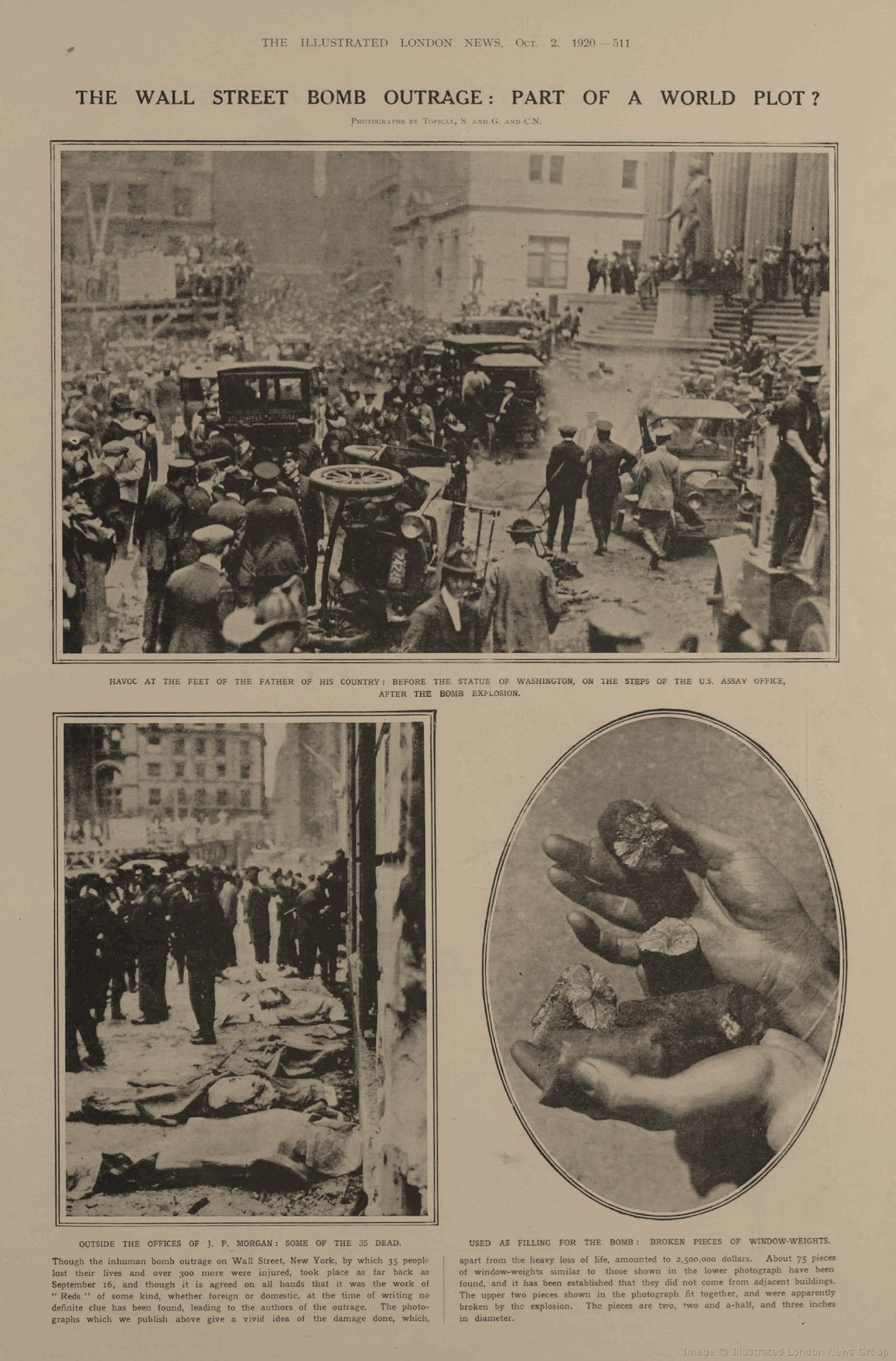

The deadly bombing of Wall Street in 1920 killed 38 people and left hundreds wounded. Anarchists were blamed although nobody was ever tried for the terrorist attack.

16th September 1920. A bomb explodes at lunchtime outside the J.P. Morgan Headquarters on 23 Wall Street. Killing dozens.

The solid granite facades of the Stock Exchange, the Sub-Treasury building, the Assay office and John Pierpont Morgan's Bank spoke of a permanence and stability that belied the insecurity faced by many American workers in the fall of 1920. The American economy was wracked by high unemployment and sharp inflation.

William Joyce, a 24 year-old a former First World War veteran and Head Clerk at J.P. Morgan Bank, glanced out the window at the scene outside. The busiest intersection was in New York City's financial district was filling with office workers heading out for their lunch break. (Bruce Watson)

Lawrence Servin made a living as a chocolate peddler, selling chocolates to the noon-time crowd while keeping one eye out for cops. In 1920, it was not uncommon to see horses and carts on the streets of New York, though few were as dilapidated and old as the wooden wagon pulled by a tired old horse.

The horse pulled up in front of the Assay office, across from J. P Morgan's headquarters. The driver quietly slipped off the wagon and briskly walked away.

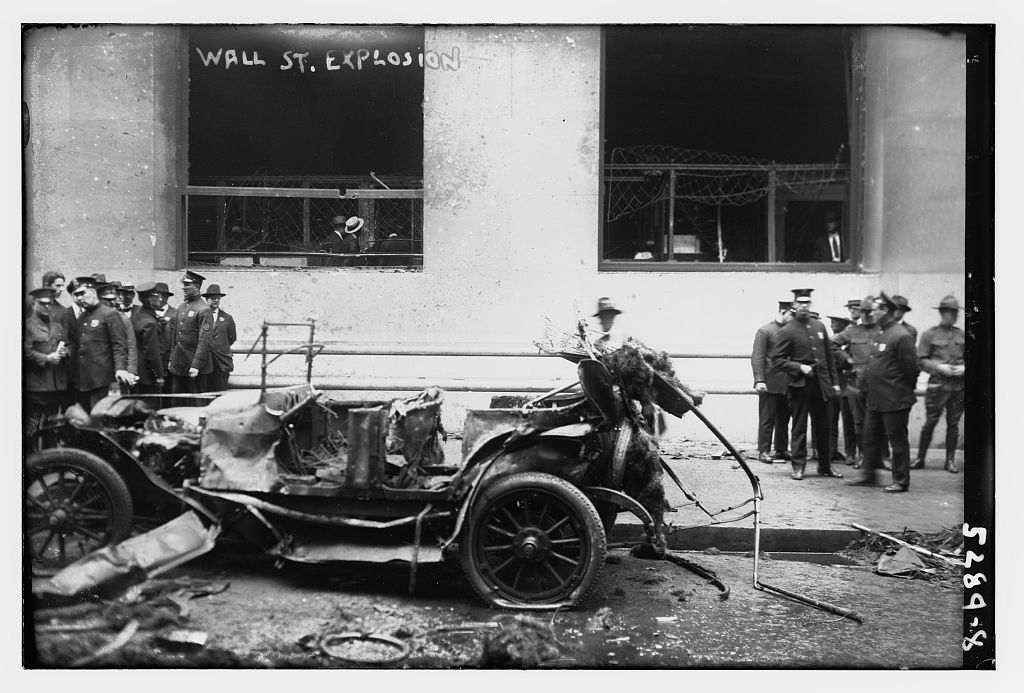

At 12:01 p.m. as the last notes of the bell's from Trinity Church died away, came a tremendous shattering explosion. The sound of the blast, shaked the mighty buildings to their foundations.

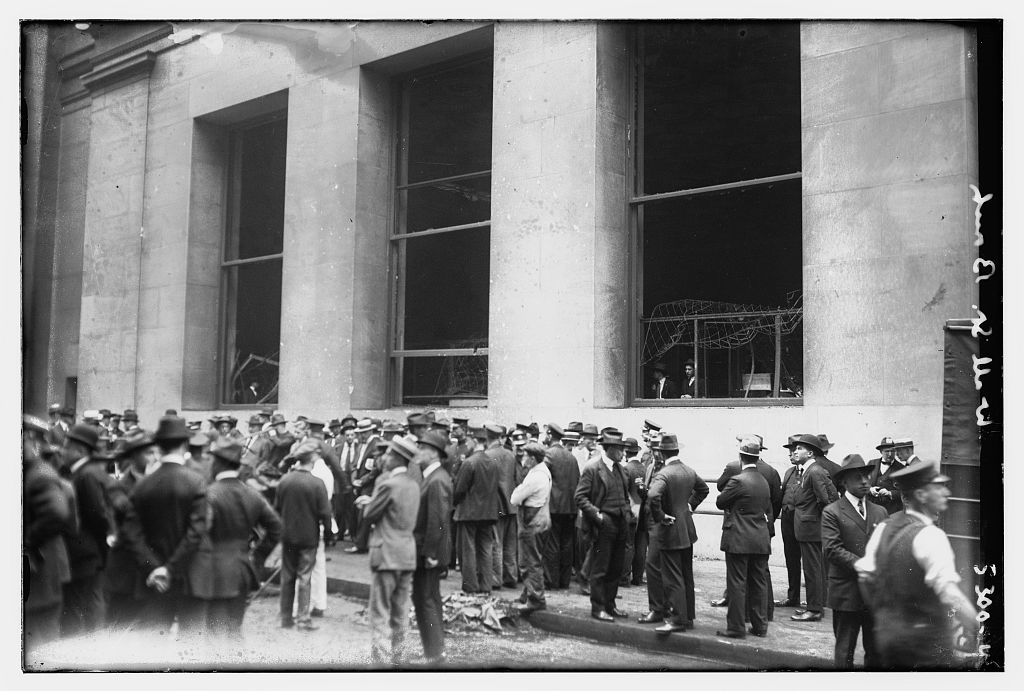

Those unlucky enough to be in the area were trapped in the carnage. Hundreds of people, knocked off their feet. Automobiles thrown into the air and overturned. Blood spattered on the walls and sidewalk. Windows shattered from ground level to nine stories high. Flying glass injured Ulysses S. Grant, grandson of the Civil War General and President, who worked in the sub-Treasury building. (Which by co-incidence, $1.8M in gold had been transferred to. But no attempt at robbery took place.)

Many World War I veterans, suspected that the "inferno" wreaked such destruction, it had come from the skies. The delivery system – was the horse drawn wagon.

The shattering glass, which one witness said covered the inside of the J.P. Morgan office ''like snow,'' was not as deadly as the chunks of hot metal projectiles slamming into the side of the building, biting holes into the smooth facade. One of the hot slugs killed William Joyce at his desk.

William was supposed to be on honeymoon but had postponed his wedding until October to cover for a colleague on vacation.

James Saul, an Office Boy, initially knocked flat by the bomb blast. With his ears ringing and spattered with blood, some his own. Commandeered an empty automobile and loading the injured, making four trips to Broad Street Hospital. Lawrence Roberts, a Salesman, was comparatively lucky, escaping with a broken leg. Many of the injured lay unconscious on the pavement and others twitched in their death throes.

Hundreds of panicked office workers ran away from the devastation. Even more people were drawn towards it by the noise of the explosion, heard all over Manhattan.

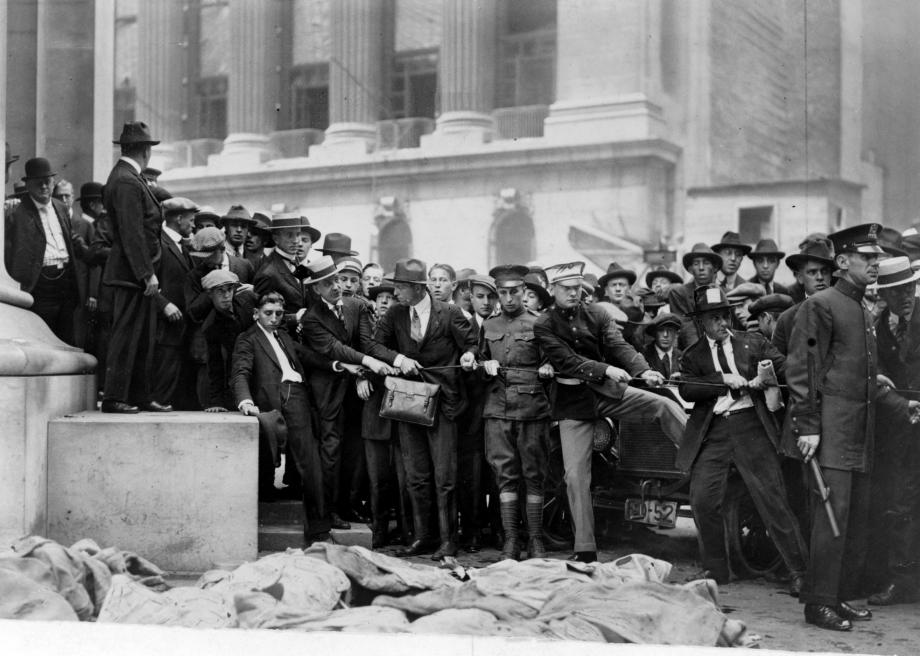

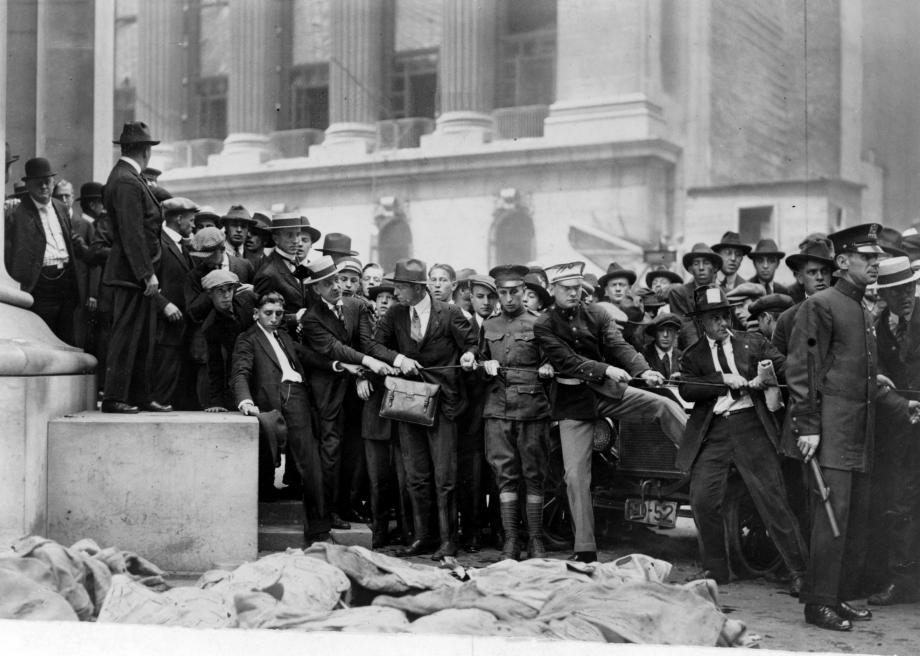

Ambulances and firemen raced to Wall Street, now covered with broken debris, glass and maimed bodies. Rescue workers lined up a row of corpses covered with car blankets from automobiles. It would be the deadliest terror attack on American soil until the Oklahoma City bombing 75 Years later.

By nightfall, the death toll stood at 31, with hundreds more injured. Dorothy Hutchinson learned that her husband William Joyce, would not be coming home.

The majority of victims were chauffeurs, couriers, secretaries and bank tellers – ordinary working-class people. Some American, others from England, Ireland, Poland and Sweden.

100 pounds of dynamite, the kind used in demolition work, had been wired to a timer and packed with 500 pounds of small chunks of iron. (Watson)

A woman’s head was discovered stuck to the concrete wall of a building, with a hat still. There was a tangle of twisted metal and a large depression in the roadway where the horse stood. The head was found not far from the blast, but its hooves turned up blocks away in every direction.

One survivor noted the statue of George Washington on the steps of the old subtreasury building. “Looking down from its pedestal between the granite columns, scarred by missiles from the explosion, the outstretched hands of the Father of His Country seemed to carry a silent command to be calm."

Lawrence Servin, the chocolate peddler, regained consciousness in the hospital. He told police that he had seen the driver of the wagon and described him as a ''dark- complexion, unshaven, between 35-40 years old, dressed in work clothes and a dark cap.

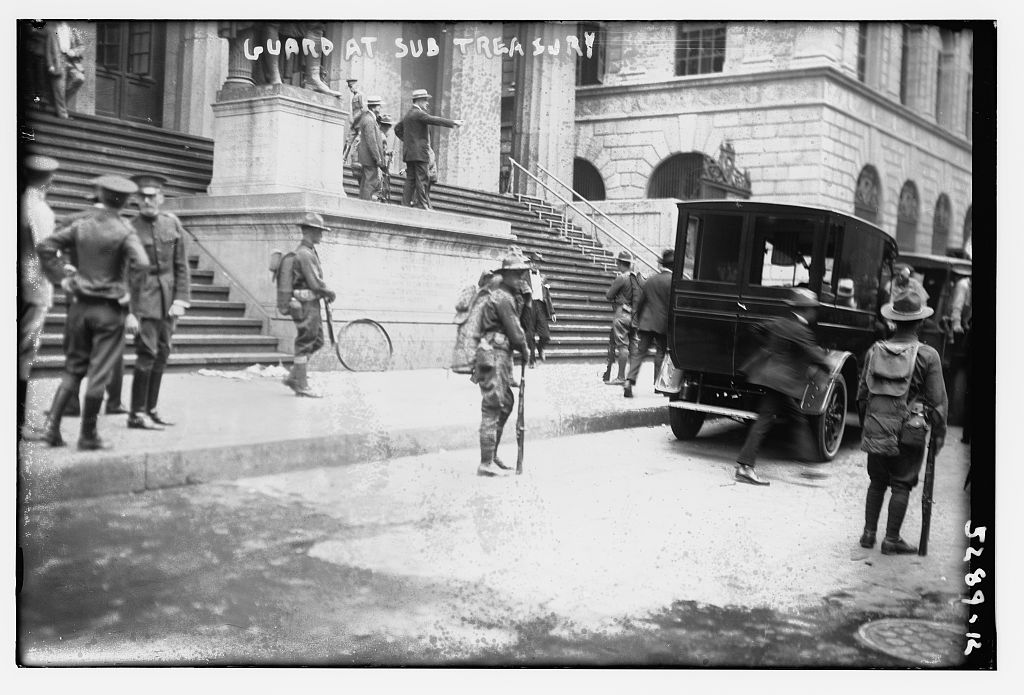

Remarkably, the Stock Exchange opened as usual at 10 a.m. the next day. Financial leaders at Wall Street were determined to put on a display of strength in the face of the attack and show life would go on as usual.

The carnage, was swept and washed away. Broken windows were draped in canvass. Workers returned wrapped in bandages. So quick had the debris been removed the police had to chase down barge-boats carrying garbage to search for remaining bomb and wagon fragments or other clues. (Beverley Gage 2009)

William J. Flynn, head of the Justice Department's Bureau of Investigation, arrived from Washington with scores of federal detectives. At police headquarters, Arthur Carey, chief of the homicide squad, asked for harness makers, livery stable owners and wagon builders to help him reconstruct the shattered wagon and identify the maker of the horse's shoes. Although hundreds of City detectives and federal agents worked on the case. They were no firm leads.

Wealthy New Yorkers hired private security to guard their homes. J.P. Morgan, who was on vacation in Europe at the time of the bomb blast, hired his own detectives to find the killer.

Detectives sorted through hundreds of leads, rumours and hoaxes. Letters and postcards warned of further bomb attacks across America. Several letters warned of the explosion, were traced to a man living in Canada known to be suffering from paranoia. A bizarre coincidence that he predicted an explosion on Wall Street...

But the day after the bomb blast postal inspectors found a message in a mailbox a block away from the explosion appearing to come from the terrorists:

Remember we will not tolerate any longer free the political prisoners or it will be death for all of you. American Anarchists Fighters!

The mailbox was emptied around 11:30a.m. each day. Detectives reasoned the terrorists had dropped their message on their way to detonating their bomb.

Before the last of the victims were buried, newspapers declared that investigators had run out of leads in their search for the perpetrator. In fact, Flynn and the NYPD had a very good idea of who was behind the explosion – what they lacked was proof.

Previous explosions in New York City prior to 1920

Almost exactly previous, on 11th September 1919. A series of violent explosions broke hundreds of windows, terrifying thousands. The cause was attributed to sewer gas. The quarter containing the principal hotels in New York and Grand Central Terminus, the gigantic station with 83 platforms.

It's proximity to excavations, the building also suffered serious from explosions. In 1910, 13 persons were killed and many declared missing. A leaky gas tank, used to supply railway carriage, caught fire. This ignited large quantities of dynamite. In moments a score of workmen were buried in the ruins of the half built station.

A few months later another accident, caused by dynamite. It killed more than 20, injured hundreds and caused damage for a radius of 30 miles. A barge loaded of dynamite off a New Jersey pier across the Hudson River blew up. Dynamite was used for all excavations due to the rocky nature of Manhattan.

Remarkably, 30 explosions occurred in New York in just one day in July 1916 causing $5M of damage.

They happened at a time when accidents of a similar nature were being reported from all over the United States as the result of plots by German agents.

Why was there going anger towards Wall Street in the late 19th century?

On December 4, 1891, a poorly dressed man named Henry Norcross carried a brown satchel into the reception of office 71 Broadway in lower Manhattan. Claiming he had an important matter to discuss with Russell Sage, a wealthy financier and railroad executive. A clerk, William Laidlaw, explained that Mr. Sage was in a meeting and very busy, but Norcross persisted “in a loud tone,” according to the New York Times, and Sage finally emerged to see what all the fuss was about.

“I demand a private interview with you,” Norcross told him.

Sage explained that such a meeting was impossible, so Norcross handed him a letter demanding $1.2 million. When Sage ordered him to leave immediately, Norcross dropped his dynamite-filled satchel to the floor. The explosion killed the bomber and injured Laidlaw, another clerk and Sage.

Laidlaw, who was disabled for life, sued Sage, alleging that the tycoon had used him as a human shield in the blast. He won nearly $70,000 in civil judgments, but the notoriously stingy Sage fought him in court. Laidlaw never collected a penny.

Among working-class Americans, Henry Clay Frick's actions at the Homestead Steel Strike of 1892, where he was the Manager were condemned as excessive. Striking workers, some armed, had locked the company staff out of the factory and surrounded it with pickets. Frick was known for his anti-union policies. As negotiations were still taking place, he ordered the construction of a solid board fence topped with barbed wire around the mill. Frick refused to speak with union representatives and threatened to have striking workers evicted from their homes.

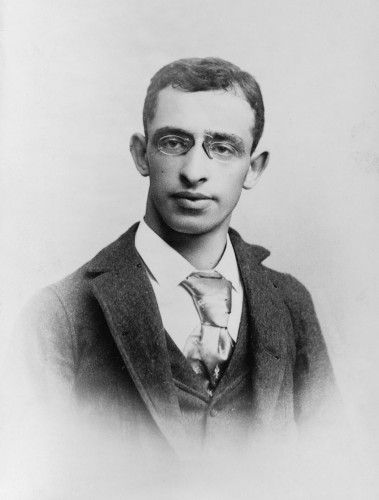

Alexander Berkman, a 22-year-0ld, Lithuania-born anarchist living in New York with Emma Goldman, set out for Pittsburgh to make a statement against capitalism. By assasinated Frick. Armed with a pistol and poisoned steel file, Berkman gained entry to Frick's office, shot the wealthy industrialist three times and stabbed him with the file before workers pulled him off and beat him unconscious. Frick recovered.

Berkman served 14 years in prison for attempted murder. Public opinion, horrified with the attempted assassination resulted in the collapse of the strike. Thousands of steelworkers lost their jobs with strike leaders, blacklisted. Those who managed to keep their jobs had their wages cut in half. (Gilbert King)

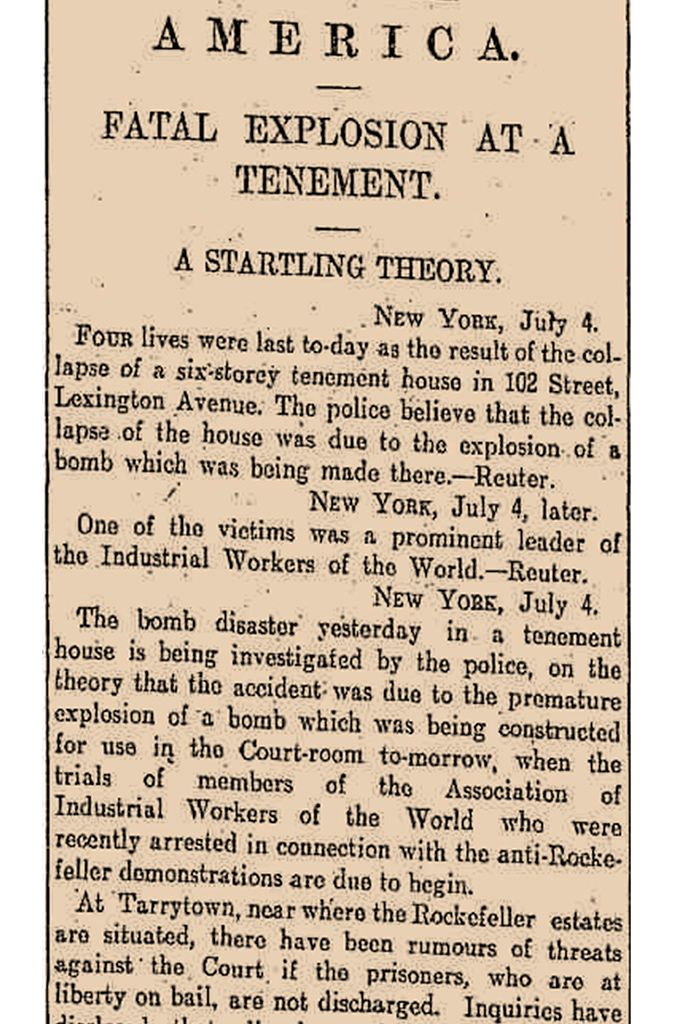

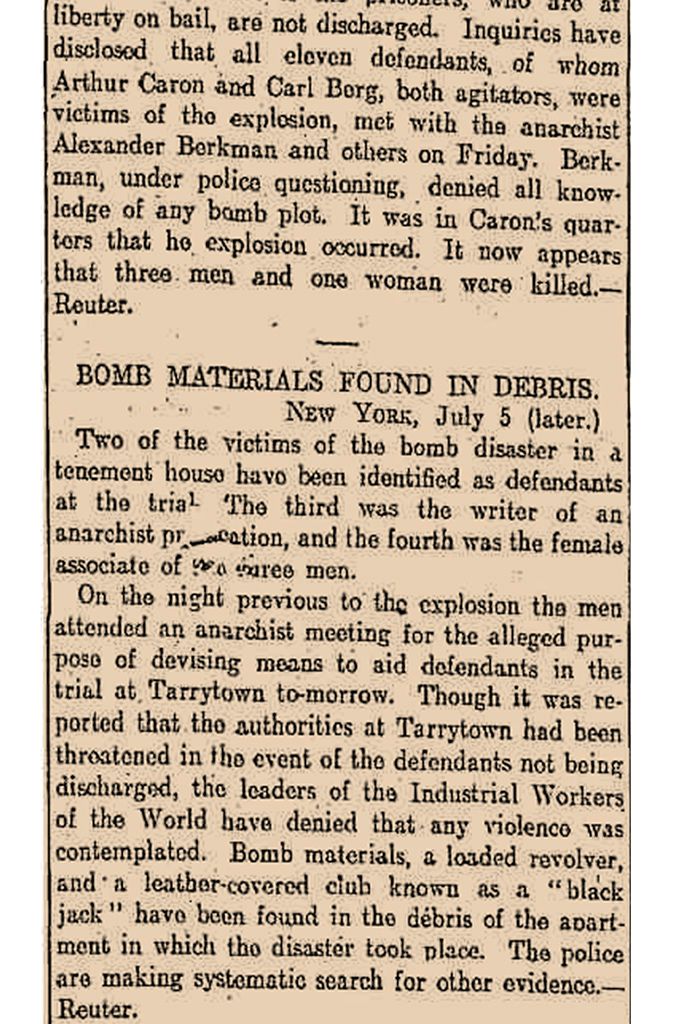

Berkman was believed to be one of the failed plotters in the 4th July 1914, Industrial Workers of the World’s (IWW) attempt to place dynamite in the New York home of John D. Rockefeller. They had blamed him for the Ludlow massacre. The deaths of striking workers and their families at a Rockefeller-owned mine in Colorado earlier in April.

A Latvian sect from the anarchists of the Anarchist Black Cross had been storing dynamite on the top floor of seven–storey tennemant at 1626 Lexington Avenue on the corner of 103rd Street. It exploded prematurely just after 9:00 a.m. killing three anarchists including Arthur Caron, Carl Berg, the girlfriend of one and injuring fellow residents.

The three had attended the previous Friday night's meeting at Francis Ferrar Association’s School, where Leonard Abbott, President of the Free Speech League; Alexander Berkman, had been at the demonstrations in Broadway and Tarrytown, and talked over a return to Tarrytown on Monday.

The bomb blew off the southern part of the three upper floors of the building and had hurled part of one man over the roof of a German evangelical church next door and on to the pavement of 103rd St, half a block north.

“Lexington Avenue and the thickly populated streets in the neighborhood were crowded with men, women, and children on their way to seashore or park to spend the holiday, when suddenly there was a crash like that of a broadside from a battleship,” wrote The New York Times.

The roof of the house was shattered into fragments and the debris of the three upper floors showered the crowds. Some three blocks away.

The Scotman in the UK, reported that the bomb: '... was being constructed for use in the courtroom tomorrow, when the trials of members of the Association of IWW... recently arrested in connection with the anti-Rockefeller demonstrations were due to begin.' And '...eleven defendants of whom Arthur Caron and Carl Berg, both agitators, were victims of the explosion, met with the anarchist Alexander Berkman and others on Friday.'

The anarchists were identified with the disturbances near Rockefeller’s home at Tarrytown.

A week later, about 5,000 people came to Union Square to hear a tribute to the would be bombers. As officials investigated, Berkman would initially deny any involvement. He would later admit he was aware the bomb was destined for Rockefeller’s estate.

In 1906, Eric Muenter, a German professor at Harvard, but actually a spy and a "fanatic" of the Imperial German government. He poisoned and killed his pregnant wife with arsenic. He appeared again as Cornell University professor "Frank Holt" who contacted the German spy network who sabotaged US aid to the war in Europe against Germany. He would spend the next decade on the run from Police.

Outraged in his belief that J.P. Morgan was profiteering from World War I by organising a syndicate of 2,200 banks lending money to Allies, Muenter hoped to put an end to World War I single-handedly. After traveling with explosives to Washington D.C. by train, Muenter planted a time bomb in a reception room in the empty Senate building. It detonated causing no casualties but demonstrated the power of explosives.

He boarded a train back to New York and made his way into the Morgan mansion in Glen Cove on Long Island, intent on persuading the banker to cease munitions shipments abroad, and shot Morgan twice before servants subdued him. The banker recovered. Muenter would later kill himself in prison. (Ron Chernow)

Five years later, 16th September, 1920, a red wagon filled with dynamite and sash weights rolled up to the fortress-like stone structure of 23 Wall Street.

These countless stories before the Wall Street bombings would serve as a precursor to the period known as the 'Red Scare'.

What was The Red Scare?

The period between 1917-1920 marks the period of the Red Scare. President Woodrow Wilson faced trying times. The nation had come through the World War I and the deadly Spanish Flu pandemic. Returning soldiers clashed with immigrants for jobs. Newspapers were full of stories of labour unrest and general strikes. Wages were not keeping up with inflation, deadly race riots broke out in Chicago and St. Louis. Crime was rapidly on the rise.

As if that wasn't enough, small vocal groups of socialists, communists and anarchists fervently preached the downfall of the corrupt capitalist system and the coming revolution of the working-class revolution.

Sound familiar a hundred years later?

Wilson, kept a clamp on vocal opposition to the war by passing the Espionage Act, which prescribed prison terms and fines for anyone who spoke out against criticised the armed forces or otherwise gave aid and comfort to the enemy.

The 1917 Espionage Act was followed by the Sedition Act of 1918 which forbid ''disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive language,'' against the U.S. government. These laws were still in force in the summer of 1919 when Wilson appointed fellow Democrat A. Mitchell Palmer as his Attorney General.

Several months later, Wilson had a stroke and was incapacitated for the remainder of his presidency. Many of the nation's problems fell on Palmer, including the problem of what to do about radicals, many of whom were illegal immigrants.

Palmer's Justice Department included the Bureau of Investigation, now known as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Director William Flynn, a former New York City detective, was put in charge of surveilling and catching radicals. One of Flynn's assistants, was a fast-rising young civil servant named John Edgar Hoover. (Beverly Gage)

Hoover meticulously assembled and organised information on thousands of cross-referenced index cards. Palmer would boast 'Every anarchist or red in the country is ticketed and labeled like dry goods. He can be reached at any time'.

The American public seldom distinguished between anarchists, socialists and communists, dubbing them all 'Reds' or 'Bolshies'. Anarchists like Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman were the first to denounce Lenin's Bolshevik revolution because they opposed his totalitarian methods. Anarchists are against any formal organisational structure.

The Haymarket bombing in which eight policemen died was the work of anarchists. An anarchist assassinated President William McKinley in 1901.

Italians who migrated to communities up and down the East Coast were devoted anarchists. The foremost Italian anarchist in America at that time was Luigi Galleani, a charismatic orator who believed that violence was necessary to overthrow capitalists. Galleani emigrated from Italy in 1901 and lived in New Jersey. Flynn called him the cleverest of the anarchists. The members of Galleani's inner circle were Carlo Valdinoci, Mario Buda, Nicola Sacco and Bartolemeo Vanzetti.

Galleani and his disciples had a public and hidden side. They spread the gospel of anarchy through newsletters, speeches, social events and plays. An inner cadre used bombs to get their message across. Four Galleanists died while planting a bomb in a Massachusetts textile mill. A female member of the group was arrested on a Chicago-bound train with a satchel full of dynamite. Galleani himself was arrested several times for inciting labor unrest and advocating anarchy, but was always acquitted.

This may have been in part because any judge trying anarchists in his courtroom could count on a retaliatory strike in the form of a bomb in their courthouse or home. There were scattered incidents of bombing in New York City, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Boston, and Milwaukee.

Justice officials were certain that Galleani was behind many bombing incidents. Lacking direct evidence, they could not prosecute him, but they could deport him because he was a illegal resident preaching criminal anarchy and had authored a ''how-to'' bomb-making manual, titled La Salute é in Voi (The Health is Within You).

In October 1918, Congress passed a new law, the Anarchist Act. In response, Galleani and his followers declared war on the U.S. government and announced their intentions through a published flyer: ''Deportation will not stop the storm from reaching these shores. The storm is within and very soon will leap and crash and annihilate you in blood and fire...We will dynamite you!''

In late April, three dozen small bombs destined for prominent politicians, justice officials, and financiers such as John D. Rockefeller were sent through mail. A few of the packages were delivered. Although the design of the bombs were carefully packaged to look like store samples, the plotters had neglected to add sufficient postage.

Once the authorities realised the packages marked ''Gimbel Brother's – Novelty Samples'' contained bombs, postal officials managed to intercept them. No one was killed, but when Senator Hardwick's maid opened the package sent to his home in Georgia, her hands were blown off. Hardwick was on the anarchist's hit list because he co-sponsored the deportation bill.

The anarchists intended their bombs to be delivered on May Day, the international day of revolutionary solidarity. A month later, the anarchists managed to blow up eight large bombs, nearly simultaneously, outside the homes of judges, politicians and a factory owner who had drawn their ire.

Judge Albert F. Hayden of Boston, Judge W.H.S. Thompson and Judge Charles Nott of New York sent anarchists to jail for protest and conspiracy. W.W. Sibray of the Bureau of Immigration presided over deportation hearings. In Paterson, New Jersey, a bomb exploded at the home of Harry Klotz, a powerful mill owner. The politicians on their hit list had endorsed anti-sedition laws and deportation – Mayor Harry Davis of Cleveland, Massachusetts State Reps. Leland Powers and Palmer.

This was their second attempt on Attorney General Palmer's life. But once again, none of the anarchists' intended targets or their wives and children, perished in the attacks. The fatalities were a night watchman, a female passerby and one of the anarchists Carlo Valdinoci, Galleani's lieutenant. He died in spectacular fashion when the bomb he placed at the home of Attorney General Palmer exploded in his face. (Paul Avrich pp.496)

The police collected Valdinoci's remains over a two block area. To their frustration the pieces of Valdinoci that they needed, his finger-tips, were destroyed in the blast. For some time they did not know the identity of the dead bomber, but strongly suspected he was an anarchist.

The Washington Post reported, '... the series of bomb outrages occurring simultaneously in eight American cities may now serve as a warning as to what wavering, indecision and weakness inevitably lead to in dealing with the new brand of Bolshevik-anarchy which is fastening itself like a foul growth on the life of the country.'

No arrests followed. Periodically Palmer or Flynn would announce that federal agents, working undercover, had discovered the existence of vast conspiracies aimed at overthrowing the United States government. Palmer enjoyed nation-wide support in his hunt for the radicals, as the headlines attested: 'No Mercy for Reds Behind Gigantic Bomb Plot to Main and Kill' and 'Congress to Fight Reds Who Seek U.S. Downfall.'

The Justice Department did not have authority to deport illegal immigrants, only the Immigration Department could. The Commissioner of Immigration, Anthony Caminetti, argued the anarchists were hypocrites to delay their deportations with legal appeals: 'Those who most noisily denounce every form of government in existence are the most persistent in claiming every technical and other right under the laws of the country they are in'.

Palmer, an eye on the pending Democratic presidential nominations, warned, '... the blaze of revolution sweeping over every American institution of law and order...eating its way into the homes of the American workmen, its sharp tongues of revolutionary heat were licking the altars of the churches, crawling into the sacred corners of American homes, seeking to replace marriage vows with libertine laws, burning up the foundations of society.'

With the public clamoring for action, Palmer, Flynn, Hoover and Caminetti turned their attention to rounding up and deporting as many anarchists as they could. A wave of arrests and deportations known as the Palmer Raids.

What were the Palmer Raids?

Luigi Galleani and eight associates were deported in late June 1919, three weeks after the June 2nd wave of bombings. Several dozen members of Galleani's inner circle successfully eluded the federal investigators, including Buda, Sacco, and Vanzetti who moved around and used alibis.

As many as 10,000 immigrants were swept up in the raids in late 1919. Justice officials claimed to find counterfeiting equipment. Many radical groups had their own small printing presses, as well as materials for making bombs. A typical raid took place on Aug. 14, 1919 at the premises of the Union of Russian Workers in Manhattan. Policemen from the New York City bomb squad swarmed the building arresting everyone inside. Most of the men herded into holding pens turned out to be poor Russian immigrants who were taking English classes. The authorities believed the real purpose being to gain recruits to the cause of revolution. Large quantities of anarchist literature was found secreted in various portions of the premises.

Two thousand illegal immigrants were being held, awaiting deportation when 70-year-old Assistant Secretary of Labor Louis Freedland Post intervened. Appalled by the Palmer Raids, which marked immigrants for deportation without counsel or in some cases evidence of wrong doing. He reviewed the pending deportation orders and cancelled most of them. In his memoir of the Red Scare, Deportations Delirium, he wrote Palmer's justice officials had trampled on the Constitution:

'... detectives of the Department of Justice ruthlessly invaded peaceable homes, in the small hours of the morning, without warrants but upon a pretense of imminent danger to the community and arresting inmates in their beds, searched their rooms, seized lawful private property and hurried their prisoners to police stations where, before the sun had risen, they subjected them to ''third degree'' examinations in efforts to discover evidence of a guilt that apparently did not exist. ... those detectives made sweeping arrests of whole audiences at public meetings, rounding up citizens and aliens without discrimination, and standing them against meeting-room walls, searched them threateningly after the manner of highwaymen robbing groups of travellers. They kept prisoners incommunicado, old Spanish fashion, for days at a stretch, lawlessly intercepting their letters in the mail, depriving them of the help of friends and the services of lawyers, placing them beyond the reach of writs of habeas corpus and hiding them so that their families were in distress from ignorance and fear. And the victims, those ''moral rats'', what were their offenses? Were they criminals? In almost every instance, No.' (Louis Post.)

Palmer countered that Post was defying the law because of ''his own personal view the deportation law is wrong.'' The Assistant Secretary was a ''moonstruck parlor radical'' who'd even invited Emma Goldman to his home. Palmer lacerated Post for ''his self-willed and autocratic substitution of his own personal viewpoint for the law... his perverted sympathy for the criminal anarchists of the country... his release of even self-confessed anarchists of the worst type.''

But Post wasn't the only voice to speak up against the Palmer Raids. A committee of 12 prominent lawyers, including Felix Frankfurter, issued a ''Report upon the Illegal Practices of the United States Department of Justice,'' charging that Palmer's ''ruthless suppression'' had inflamed ''revolutionary sentiment'' and created more radicals than he caught.

Palmer had enjoyed widespread support for his crusade against the 'Reds' but would suffer a dramatic reversal of his fortunes in the Spring of 1920. Only the year before, Palmer and his federal agents were the heroes who thwarted the May Day mail bombings and he was touted as a leading candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination. But now he was seen as a political opportunist. Too many public alarms were false alarms. Palmer had predicted more mayhem for May Day 1920, but the day passed peacefully. Jackson Ralston, a Washington lawyer, complained that the Justice Department 'advertised uprisings on specific dates, which failed time after time to materialise, until the whole matter became a national joke'.

Although the Palmer Raids ceased, undercover surveillance and deportation of radicals continued. Eugenio Ravarino, an undercover agent working for Flynn's Bureau of Investigation, managed to penetrate what was left of the Italian anarchist movement. Acting on Ravarino's information, federal agents began to roll up the remaining Galleanist radicals, making arrests in Brooklyn, New Jersey and Paterson. Two of those arrested, Roberto Elia and Andrea Salsedo, were of particular interest because they were printers who may have been responsible for publishing the anarchists' manifestos that accompanied their bombs. The two were held incommunicado, illegally, at Justice Department headquarters in New York and the evidence is that they were beaten. After several days of intensive interrogation, Salsedo confessed to their connections with the Galleanists and named other members of the group.

Word reached Buda, Sacco, and Vanzetti that their comrades were being held and interrogated. The remaining Galleanists concluded that their days were numbered and most, including Sacco, made preparations to leave the country. Some have argued that one of his preparations was to acquire some cash for himself and his fellow anarchists by robbing the payroll of a shoe factory in South Braintree Massachusetts, where he briefly worked.

Meanwhile, Salsedo flung himself out of a 14th story window at the Justice Department. Flynn lamented that Salsedo's death hampered the investigation of the bombing campaign. The next day, Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested and eventually charged with armed robbery and murder, resulting in the most hotly debated trial of the 20th century.

The Trial of Sacco and Vanzetti

Sacco and Vanzetti were indicted on Sept. 11th. Five days later Wall Street exploded.

Sacco and Vanzetti were not on trial for radicalism, but for killing a payroll guard and a clerk and making off with $16,000 in payroll cash. Nevertheless, it is an interesting historical question: Were they part of the bombing conspiracies of the Galleanists?

Historian Paul Avrich concludes ''... Both were ultra-militants, believers in armed retaliation. They carried guns... they were associated with known participants in the plot. [Mario] Buda reckoned them the ''best friends'' he had in America and they were equally close to Valdinoci, the man who died while planting a bomb.''

The night Sacco and Vanzetti were detained, they were questioned about their radical activities and associates – not the South Braintree payroll robbery. They assumed that they had been caught in the dragnet for anarchists and lied. They also told their lawyer that they were hiding a cache of dynamite that night and were lying to cover their tracks.

Even though they were not on trial for their anarchist beliefs or any terrorist activities, the defense strategy was hopelessly compromised. From the point of view of saving Sacco and Vanzetti's lives, the defense attorneys should have focused on the crimes themselves and shown that the prosecution's evidence did not rise to the standard of proof beyond reasonable doubt. But Sacco and Vanzetti had to explain why they had lied to the authorities. They were not covering up the participation in the robbery, they explained, they were hiding the fact that they were anarchists. But this explanation brought their anarchist beliefs into the courtroom, and Prosecutor Frederick G. Katzman took full advantage.

Sacco and Vanzetti were convicted on July 14, 1921. They were executed seven years later. The executions sparked anti-American demonstrations around the world. Rioters in Paris swarmed the streets, smashing American cars. They entered movie theaters and pulled American films out of the projectors.

It is often asserted that Sacco and Vanzetti were deliberately framed. They were initially arrested because of suspicious circumstances that pointed to their participation in the South Braintree hold-up. One of their associates, Feruccio Coacci, had missed his April 15th deportation sailing but voluntarily left the country immediately thereafter. Coacci lived near South Braintree and Chief Michael Stewart, who was investigating the April 15th murder, wondered if there was a connection. The stolen car used in the robbery was found abandoned near Coacci's home. The police went to Coacci's home to investigate and found Mario Buda living there. Buda gave them a false name and disappeared after being questioned. The police learned that Buda had left his own car in a local garage and they asked the garage owner to let them know when he came to pick up his car.

On May 5, Buda and three other men showed up at the garage. The garage owner told them they couldn't drive the car because it didn't have a current license plate. While his wife slipped to a neighbor's house to phone the police, the men reluctantly left. The police sent an officer over. Although Sacco and Vanzetti had lived in the United States for 12 years, their appearance and demeanor made them instantly visible. When arrested, they were both carrying guns. Vanzetti's gun was said to match the gun stolen from the slain payroll guard. Three different brands of bullets were used in the robbery. The same three were found in Sacco's pocket.

They told friends they would have proudly died for anarchism, but to be executed for a sordid murder and a grubby robbery was a different matter.

Tito Ligi and Giuseppe de Fillipis matched the survivors' description of the driver, while Florian Zelenko was arrested with dynamite in his possession. They were all released ''for lack of adequate evidence.'' Flynn and the NYPD conducted a diligent and thorough investigation, including placing an informer next to Sacco's cell.

On the first anniversary of the Wall Street bombing, Flynn publicly discussed the Justice Department's theory that the bombing was the work of ''the so-called Galliani band that was centered in Paterson, New Jersey, but whose members became widely scattered.'' He suspected that Galleani himself, by then deported to Italy, ordered the strike. Decades later, an old associate of the Galleanists told historian Paul Avrich that Mario Buda was the driver of the wagon that blew up Wall Street. This fits what is known about Buda's movements at the time. But Buda was beyond the reach of Bureau of Investigation – he left the country after the bombing and returned to Italy. In 1927, the Mussolini government arrested him as a ''dangerous anarchist'' and sentenced him to five years in prison.

The Italian anarchist movement in America was shattered by the Palmer Raids. There were a few final salvos from the anarchists – in the years following Sacco and Vanzetti's trial, bombs went off at the homes of a witness, a juror, and Judge Thayer. No one was killed. But there were no further fatal domestic terror attacks on U.S. soil until the 1970's and the emergence of a Puerto Rican independence group and the radical Weathermen.

The legacy of the ''Red Scare'' era includes the American Civil Liberties Union which was founded to assist conscientious objectors in World War I and to protest anti-sedition laws that curbed free speech.

A. Mitchell Palmer failed in his effort to win the 1920 Democratic presidential nomination. He resigned as U.S. attorney general in April 1921. William J. Flynn resigned as head of the Bureau of Investigation in September 1921. His assistant John Hoover, became chief of the FBI in 1924 and remained, remarkably 48 years in the post until his death in 1972.

In 1961, the Massachusetts State Police ran modern ballistics tests on Sacco's pistol and concluded that his gun was indeed used in the South Braintree robbery.

Is there a memorial to the 1920 Wall Street Bombing?

Today only pockmarks from the bomb blast are visible on the facade of 23 Wall Street. Thousands of New Yorkers returned to work at the scene of the blast to sing “America,” led by a World War I veteran the next day.

Brigadier General William J. Nicholson made a patriotic speech: “Any person who would commit such a crime or connive in its commission should be put to death,” he said. “He has no right to live in a civilized community. Such persons should be killed whenever they rear their heads, just as you would kill a snake!” (Howard Zinn)

A band, with fife and drum, played “The Star Spangled Banner.” The crowd sang along as the stock market soared—an indication, many were convinced, that anarchy would never stand, and that as America entered the 1920s, the economy was poised to roar.

References:

- Wall Street Bombing 1920. Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Bain News Service photograph collection.

- The Battle for Homestead, 1880-1892; Politics, Culture and Steel by Paul Krause.

- A People's History of the United States: 1492-Present by Howard Zinn.

- Rebel in Paradise: Biography of Emma Goldman by Richard Drinnon

- Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman and Henry Frick. Wikipedia and Wiki Commons Media.

- Lona Manning, Sam Houston State University, Texas USA.

- The Day Wall Street Exploded by Beverly Gage.

- Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background by Paul Avrich.

- Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America by Paul Avrich.

- Sacco and Vanzetti: The Men, the Murders and the Judgement of Mankind by Bruce Watson.

- Hopeless Cases: The Hunt for the Red Scare Terrorist Bombers by Charles H. McCormick.

- After 1920, The Opposite of Never Forget, No Memorials on Wall St. for attack that killed 30 by James Barron, The New York Times.

- The House of Morgan: An American banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance by Ron Chernow.

- Anger and Anarchy on Wall Street by Gilbert King; Smithsonian Magazine.

- The Day Wall Street Exploded, Paperback by Beverley Gage WS

To receive a weekly roundup of new posts subscribe here. Any donations go towards funding research, reporting, independant video servers and growing the site. Thank you, Rajesh.

Bitcoin Wallet: 3Dzp87Gz7EhtQpHSYCBTSMN81GMeCQgAtm

Leave a Paypal Tip